Exhibition view, Marianne Mispelaëre, photo © Objets pointus

FAIRE CONNAISSANCES

Knowing (each others)

Solo show by Marianne Mispelaëre at Ygrec-ENSAPC Art Center

In collaboration with Le bureau des heures invisibles (bhi)

18 September to 9 November 2024

From 2020 to 2022, Marianne Mispelaëre led a collective and collaborative project in Marseille through the Nouveaux commanditaires (New Patrons) program : Les langues comme objets migrateurs (Languages as Migratory Objects) (arts outreach – prod. thankyouforcoming). She worked with teachers of French, German and literature, and a scholar in language education. Fourteen classes of youths from the Vieux Port Middle School, René Caillié High School, and Victor Hugo High School, worked with the artist with the support of their educators.

The project started with the question : what does it mean to study in a French public school today as a plurilingual teenager or as a student living in a multicultural environment? Students, aged 11 to 18, inspired, supported, and guided Marianne Mispelaëre in her research. While many of the youths involved in the project were born in France, many of them are plurilingual, and others, newly arrived, are learning French. Together, through the lens of the children’s language practices, they discussed and engaged with questions of plurilingualism, multilingualism, exile, transmission, history, creolization, translation, and identity.

Several works were produced emerging from the complexities of the project. Écrire dedans sa langue (To write “fromwithin” your language) was created as a protocol. Additional works include the film Un œil sur ta langue (An eye on your tongue), the typeface La Marseillaise (The Marseillaise), the protocols Comment vois-tu le monde à travers ta langue? (How do you see the world through your language?), and Être un être traduit (Being a translated being).

The exhibition at Ygrec-ENSAPC Art Center takes this commission in Marseille as a starting point. Engaging with these questions the following conversation involves :

- Guillaume Breton: Artistic Director of Ygrec-ENSAPC Art Center

- Sarina Basta & Amélie Mourgue d’Algue: Curator and artist, founding members of the Bureau des heures invisibles (BHI)

- Marianne Mispelaëre: Artist

Guillaume Breton, Sarina Basta, and Amélie Mourgue d’Algue: Marianne, could you begin by telling us about the exhibition Faire connaissances (Knowing (eachothers)) and how it relates to the New Patrons project you led in Marseille between 2020 and 2022?

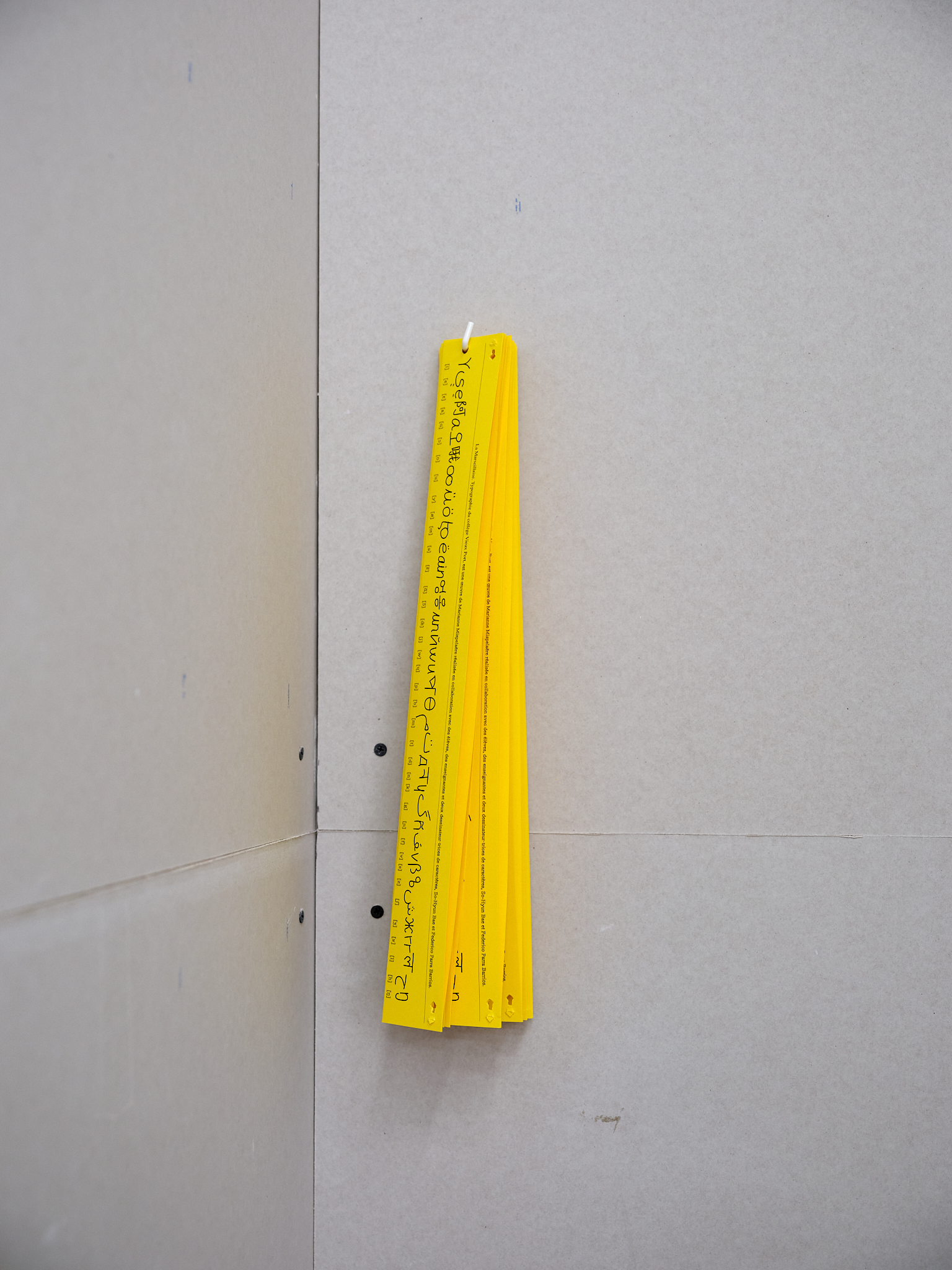

Marianne Mispelaëre: Rather than being a mere overview of the project, this exhibition is the next step in a collective thought process. I was wondering how to display within an art context works originally intended for teachers and students. Also, I had to think how I could share living and changing works, entangled in relationships that are fluid and cannot be fixed ? For Knowing (eachothers), my proposal navigates between languages, codes, and communication systems. I built the exhibition with the New Patrons project in mind—its artistic, relational, and political stakes, and the works that were created. I also considered how these works would fit within the contemporary art space of Ygrec, located in Aubervilliers—a city I love, where I live, and where my studio is located. Aubervilliers shares many similarities with Marseille. The exhibition is a continuation that invites something to persist: some works are meant to be activated on-site, while others can be taken away (such as the five protocols produced in Marseille and the stencil ruler from the Marseillaise typeface).

GB: The exhibition’s title has multiple meanings as well. Knowing (eachothers) suggests both meeting and creating knowledge, transmission, and collaboration. You worked in schools in Marseille, and the works were handed over to those commissioning the project (eight teachers, three students, and a language didactics researcher) in 2022. Do you know how the works evolve in these schools today? Are there any activations you are contemplating? envisioning or hoping for?

MM: We created the works together, my commissioners and I, along with the 257 students I worked with throughout the project. Their role now is to activate these works, and my role is to step away (laughs)! Their autonomy, the fact that these works can exist without me, is part of the project. The works were entrusted to the schools, accompanied by various transmission documents, so they can be activated with new classes, without a time limit. The works only exist if their protocols are activated, and it’s up to each person to bring them to life, offering unique interpretations. Then I can’t predict or even imagine what these activations will create in each person.

For me, something is also happening elsewhere: thanks to this project, attention is being paid, debates are possible, and questions are being raised, giving visibility to languages that are typically marginalized within the institution. Here, spoken language itself is already performing : it acts. It gives a space to marginalized languages and cultures. Even before the protocols are activated, the project makes these languages exist in the school.

GB: This also helps deconstruct the hierarchy between languages – those that are more or less spoken, or privileged in a country, institution, or education system. In a way, your work deconstructs the concept of “national identity” and reminds us that it’s plural, multiple, and certainly not confined to the French language.

AMA: We all carry multiple identities that coexist. Thanks to your work with the students, the institution becomes more aware of their plurilingualism and their unique experiences of living in and between languages.

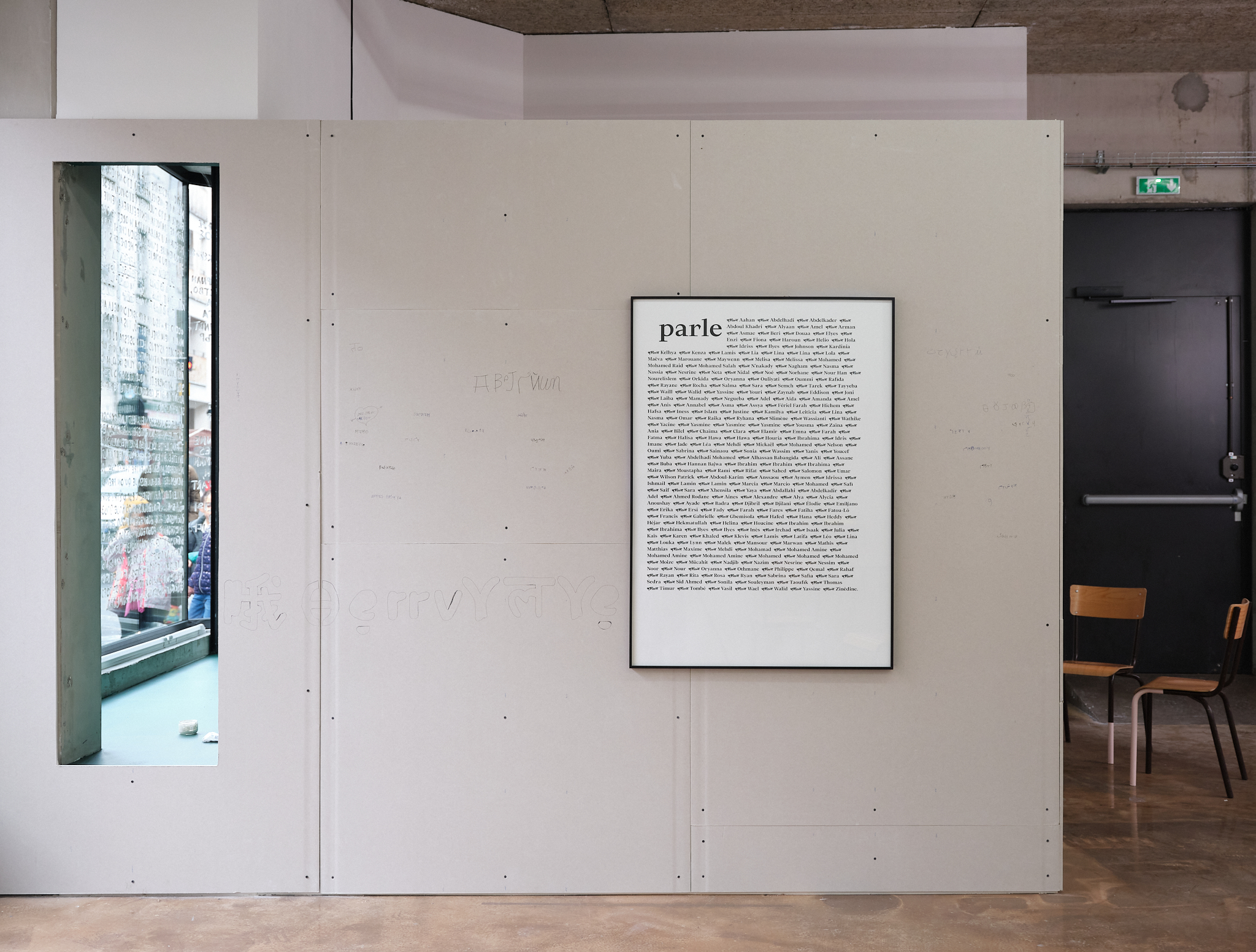

MM: Yes, identities, like languages, are fluid. They elude us as much as they construct us—this is the experience reflected in the protocol Being a translated being. They are porous, influencing one another, which is why I prefer to talk about multilingualism and multiculturalism with the adverb “with” rather than “between.” These children live with several languages, which intertwine, merge, and coexist. Timur, Alycia, Sedra, Erika, Hekmatullah explain this beautifully in the film An eye on your tongue, whose words fill the space at Ygrec. The film’s sound plays in the main room, and we only see the images afterwards. This scenography encourages us to truly listen. It gives materiality and weight to these voices.

There’s also a porosity between the “inside” and the “outside” – between home and school (or, here, the public space at Ygrec, with its large windows). My commissioners really wanted the home languages not to remain at the school’s threshold, believing that bringing to life the multiculturalism and plurilingualism present in their classes would benefit everyone, both relationally and pedagogically.

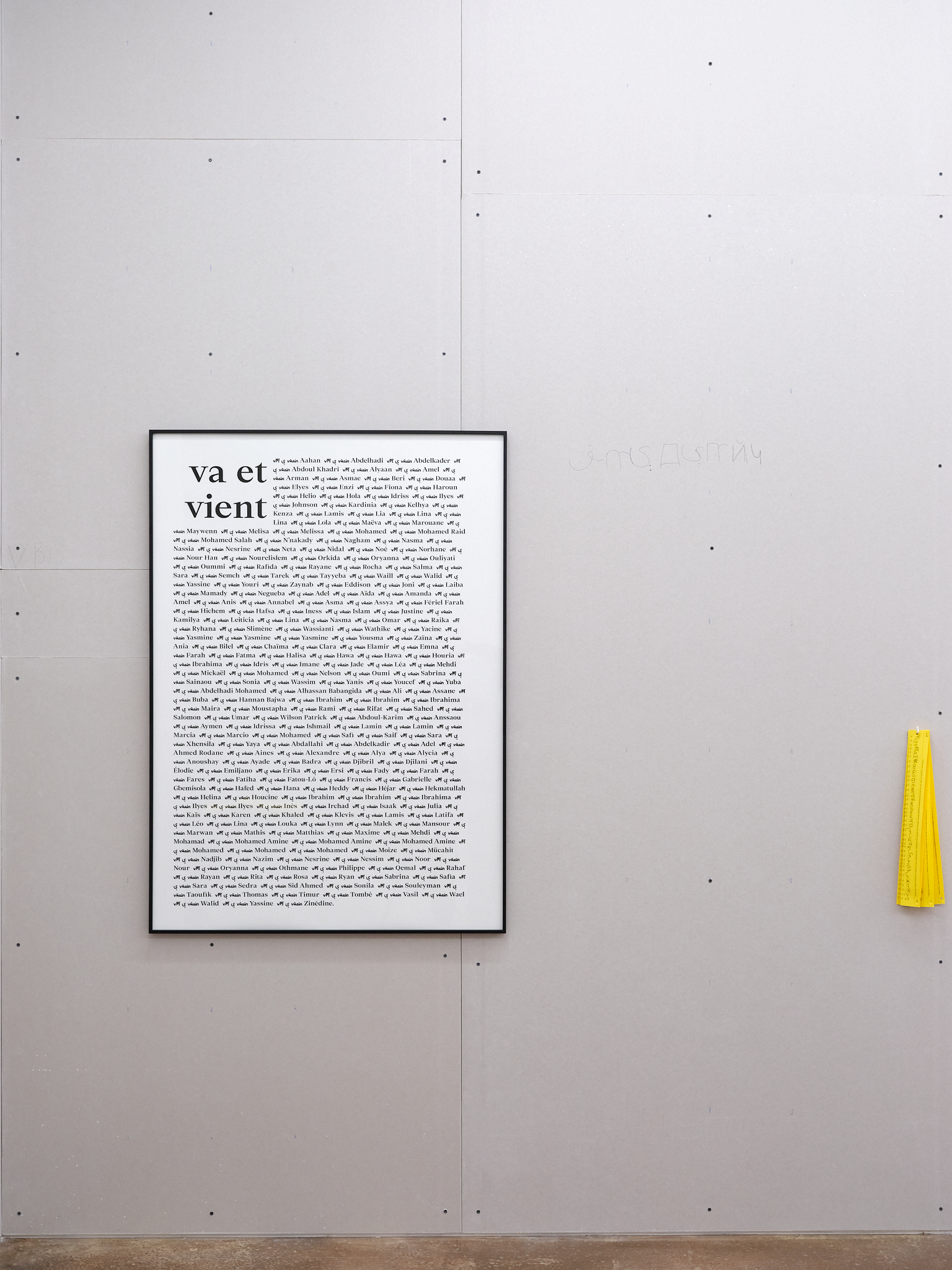

SB: Your approach invites us to create new inclusive codes, like with The Marseillaise, which will be presented in the exhibition. This typeface allows French to be written using various alphabets from different languages. Can you tell us more about it?

MM: The Marseillaise is directly inspired by something a student in the UPE2A program told me: “Learning French is easy, but pronunciation is difficult.” I wondered if I could create a tool to help them learn French, while also boosting their confidence in speaking. An accent reflects a certain mastery of language, a social background, and in this case an exile, presenting them to society through that lens. I then introduced the students to the 38 phonemes (“sounds”) in French as spoken in France and asked them to find words in their own languages that contained those same phonemes. For example, the “ON” ([ɔ̃]) sound only existed in Korean among all the languages spoken in class. We had fun identifying phonemes that don’t exist in French but do in their other languages. In those moments, the roles were reversed: the student taught the class (including adults) a phoneme, and we tried to replicate it. We laughed a lot, and I was the worst at it… Later, we tried writing French words, replacing each phoneme with a symbol that produced the same sound in one of their languages. I then decided to expand this experience to the entire school, incorporating all the languages spoken there.

The typography The Marseillaise may seem abstract – we find ourselves in the position of a learner faced with a foreign code – but it is a very tangible and empirical work. All the works made in Marseille are the result of my direct observation and listening to the students.

GB: What you’re saying through this work is that a language isn’t just words. You tell us a lot about porosity, infiltration. A language means and reveals something; it communicates before the words that compose it are even spoken. The protocol of To write “fromwithin” your language starts with a quote from Édouard Glissant: “Multilingualism is not merely a scientific issue or about knowing languages, it is about the imaginary of languages. ».

MM: Language is a collective tool, but also a deeply intimate object – as suggested by the protocol How do you see the world through your language?. It allows people to “wear” their language(s), keeping them close to their skin, barely perceptible from the outside. Participants are invited to respond freely to this question by writing a text that will be printed on the inside of a t-shirt. Only the person wearing the t-shirt can read it by pulling away the collar. A language shapes our imagination. It’s about family and love – for me, language really is about love. You learn a language as a child because you want to communicate, because you’re drawn to others. As an adult, even if it’s for work, the process is the same, the same desire is there. When I think of these children, whose family languages are often neglected or even devalued by the education system (I’m thinking of Arabic, for example), I see a devaluation of their object of love and of their identities.

GB: We can feel the love you’re talking about in the invitation you make to carve our names into the walls of the exhibition space, after transcribing it in this creolized typography, The Marseillaise. It’s a tender gesture, like carving names into the bark of a tree, into stone. And there’s importance in the act, even if the trace will necessarily disappear.

MM: This experience is participatory and processual. Engraving is a forbidden gesture in school, like tagging. You’re not allowed to leave your mark – you’re just passing by. Here, however, you’re encouraged to be part of the space, to infiltrate it.

SB: I really like this use of architecture as a surface for testimony and passage, for people who are otherwise made invisible, through an act that feels like gentle vandalism. The walls as surfaces of testimony make me think of Latifa Echakhch’s work Hospitalité (2006), which you’re referring to here. And it also reminds me of Nil Yalter’s Exile is a Hard Job, where facades and windows are plastered with portraits of immigrant workers, often made invisible by the system. Do you propose other types of activations or interventions like this in the exhibition?

MM: On the large windows of the Centre d’art ygrec-ENSAPC, there’s a text written in blanc de Meudon, that translates (and repeats) in forty languages a reminder of the opening hours, but also that entering the art space is free of charge, that we can be free there, and that the only risk in crossing the threshold is being surprised. Translation is an inherently subjective and never-ending task (a “perfect translation” doesn’t exist), and visitors or passersby are invited to erase a previously written version and replace it with their own. I hope the windows will eventually look like a palimpsest where different scripts coexist.

I wanted to translate this text into all the languages spoken in Aubervilliers, but it seems impossible to list them all for now! As the two posters say, “Speaking” and “Coming and going” coexist; language and movement are inherent to life.

AMA: Aubervilliers was once described as the city of 110 languages. This project feels closely connected to Aubervilliers, which was the basis for our invitation to you a year ago. Are there any further extensions of the commission planned?

MM: A workshop will be held during the exhibition with classes from Aubervilliers, and a meeting will be organized between teachers from Marseille and educators from Seine-Saint-Denis, where everyone will be welcome to join. Additionally, an edition published by Paraguay Press will extend the project’s reach on a national level. This book is meant to be manipulated, annotated, marked up in order to activate the works by and with everyone (children and adults), within educational contexts or beyond. Initially designed to infiltrate schools, these works are now turning towards society at large…

Marianne Mispelaëre is an artist who lives and works in Aubervilliers. Her gestures are simple, precise and ephemeral, inspired by contemporary and societal phenomena. What happens between us, within us, throughout the infinite political task of coexisting? She observes and listens to social relations, language – what it does to its users, and what they do to it. She brings together bodies, languages, signs, and visual representations (images), ways of speaking, telling, and thinking about our immediate or distant environment. Her work, focusing on in situ and ephemeral projects, is often activated or interpreted by herself or others. It has been exhibited in France and abroad and has been included in numerous public collections.

https://www.mariannemispelaere.com/

The bhi (Bureau des invisibles) is a reseach collective based in la Maladrerie in Aubervilliers. Its activities in the area explore the process of “living together” and “making commons”, engaging with it through the experience of the plurality of languages. The bhi is interested in hybrid practices between visual arts, writing, performance and pedagogy and their places in the valorization, coproduction and sharing of knowledge. The organisation supports and develops artistic projects and regional, national and international programmes in connection with the plurality of languages, social and cultural invisibility, and encounters.

Centre d’art Ygrec-ENSAPC

Dedicated to the most current forms of artistic creation, Ygrec is a production and dissemination structure that places experimental and curatorial dimensions at the heart of its action. Attentive to social, cultural, and geographical boundaries and issues, Ygrec builds its activity closely linked to its territory through an innovative schedule of artistic education actions. As a space to meet, gather, exchange and discuss, its program combines exhibitions and events. Ygrec is the art center of the École Nationale Supérieure d’Arts de Paris-Cergy.

Thanks to Cécile for the translation