The interview was conducted by sabrina soyer in April 2024 for ENSAPC.

Folakunle Oshun is an artist, researcher and art curator, cofounder of The Lagos Biennial, he is pursuing a PhD at ENSAPC.

sabrina soyer: Dear Folakunle, I was glad you said yes to this interview, because you are doing a lot of things! You’re an artist and a curator, you created the Lagos Biennale in Nigeria (about which I’ll have more questions later), and also, you’re a researcher. You’re doing a PhD at ENSAPC, focusing on the architecture of state buildings converted into contemporary art spaces across West Africa, after independence. Can you tell us more about your journey, how you move from artistic practices to research practices, do you find it difficult to move between the two?

Folakunle Oshun: I started out studying Economics in the year 2001 and then dropped out once I figured I found no fulfilment in it. I then enrolled in art school at the University of Lagos to study Creative Arts with a major in Sculpture. Before sculpture was painting, something I initially found fascinating but later realised couldn’t capture what I wanted to express. I really can’t explain how I got involved in curating, but let’s just say it began as a dissatisfaction with the manner in which the art world works. abandoning my art practice was never the plan, but i guess starting a biennial in Lagos and a PhD in Paris has made things a little tricky. I try to see my practice as holistic and complementary; one thing rubs off on the other. My obsession with architecture stems from a similar obsession with sculpture and, ultimately, form. As I said, there was a dissatisfaction and general contempt for the way I saw curators defining the practice of many artists and the docility with which the artists performed their roles in this larger capitalist art market. Curating as a practice is still relatively untapped; there is still too much emphasis on exhibition-making and documentation without proper assessment of how these endeavours affect and reflect on society. In my humble opinion, architecture is one of the keys to unlocking the potentials of art and curation; you can’t keep stuffing the same old art in the same old white cubes and expect anything different. My encounters with academics at this level has influenced how I process situations; I think I now have a broader view of how the world works and how best I can shape it in my own little way. I came into ENSAPC with no expectations; I just knew it was going to be a whole lot of work, and nothing prepared me for the intensity of doctoral research. Not being able to speak French made things a lot harder. The first year began with teaching, which was a whole new experience. So, Yes, I think I’ve covered the full nine yards of artistic practice, but my heart is still with sculpture.

s.s: How did you become interested in the history of state buildings and its possible transformations ?

F.O: As early as 2013, I began travelling across the West African coastline to places like Abidjan, Accra, and Togo. I made a second solo trip to Dakar by road in 2015. These encounters sparked my interest in the urban and rural landscapes I encountered. It is safe to say that there are a lot of similarities in the urban landscape of several cities in West Africa; these similarities can be linked to their connected colonial histories and what Manuel Herz refers to as the “Architecture of Independence”—the post-independent period in the region marked the commissioning of many commemorative buildings, which had quite interesting designs. Through my research and curatorial practice, I have tried to rationalise the present realities of the African socio-political landscape through artistic engagement with these spaces and the adjoining political and economic policies that came with them.

s.s: You created the first Lagos biennale in 2017, how did the idea and the desire to create a Biennale in this city come to you? Did you feel there was a necessity for local artists and people involved in the cultural life of this city to position themselves in relation to this format of artistic event, and its history?

F.O: It is always tricky to make a case for a biennial. What is more important is the leverage the Biennial brings to a place like Lagos and the endless possibilities of creating something not constrained by external forces. The Lagos Biennial is a non-governmental artist-run institution that simply cannot be defined or contained by whatever expectations are associated with biennials. Lagos is a peculiar place that is comparable only to a few places. What we try to do as an institution is condense the artistic energy, historical narratives and creativity as honestly as possible. I feel that honesty is something missing in the world we live in today, especially the art world, so whether we call it a biennial, a festival, or even a museum, you can feel a sense of rawness and authenticity in the work we do.

s.s: Did this first edition, by the way titled “Living on the edge”, somehow affect the “edges” of this city, geographically and sociologically speaking?

F.O: The premise was to contextualise the realities of individuals eclipsed from the centre of society within the framing of the larger ecological battles a city on the edge of the Atlantic was and still is facing. There are several perspectives on what constitutes an edge, and it was quite a moment to witness the collaborations between the artists and the host community within the Nigerian Railway Corporation.

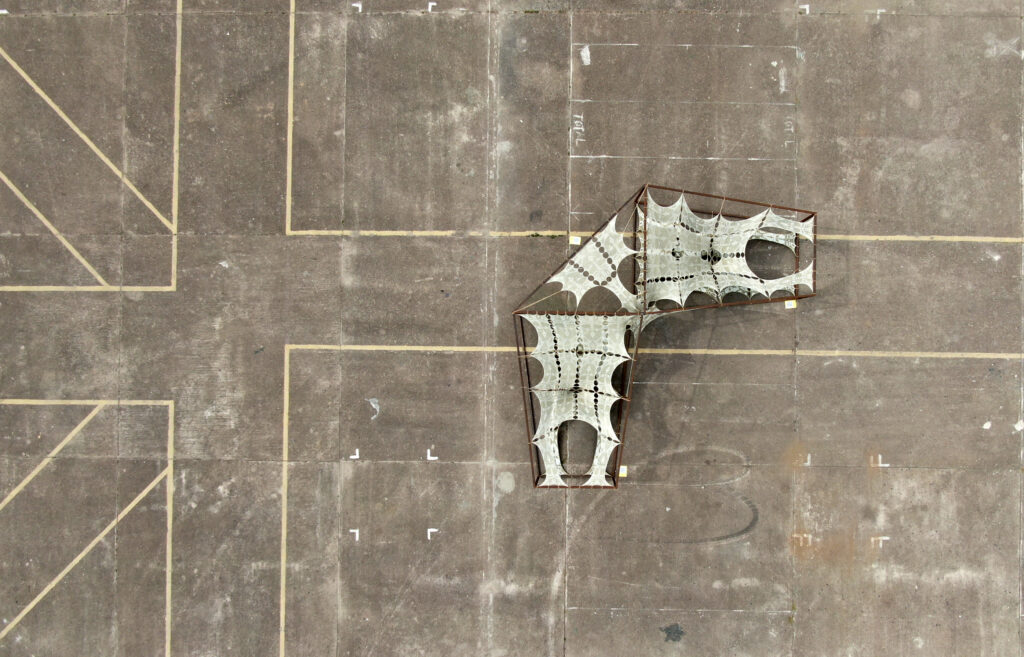

ss: In February 2024 opened the 4th edition of the Lagos Biennale, around 80 participants were invited to reflect and work around the theme “Refuge”. I dug for some pictures on the internet and saw a gigantic sign telling “Free Visa”, an installation of Kiluanji Kia Henda & Paulo Moreira. So it seems that this biennale was addressing concepts and problematics you also address in your research here in ENSAPC: the histories of the nation-state and its architectures, and how art can play a role in urbanistic, social and political transformations. Let’s also point out that this biennale took place on a historical place, the grounds of Tafawa Balewa Square, a site named in honour of the first Nigerian Prime Minister, later used as a site for the FESTAC ’77, the second edition of the World Festival of Black African Arts and Cultures. Could you tell us about the works that particularly marked you during this biennial, in relation to this site and the theme of “Refuge”?

F.O: Tafawa Balewa Square, in its overwhelming demeanour, consumed the biennial team, artists, and guests alike. In some sense, it may have consumed our narrative as the experience of a large-scale outdoor exhibition in such a historical space is rare. The physicality of engagement with art in such an expanse of concrete within a historical context is brutal enough; capturing it as a story is even more complex. It’s something that had to have been experienced in person to take its whole essence. Every piece was great, not in the way we assess great art in terms of quality, narrative, or aesthetics. But more so in the commitment and time it took to prepare and participate in such an ambitious project. I have been curating for the last 12 years and have never been involved in or seen an art event as consuming or intense as this. The sacrifices the artists made to be part of such a historic event, probably the most significant public monument on African soil, are highly commendable, especially considering the limited resources available to assemble the exhibition.

ss: Did the biennial leave any remnant of “refuges” in Lagos, materially or immaterially speaking?

F.O: The memories are lasting. Some of the pavilions have been installed in public parks and schools, and the rest live in our minds and the reassurance that there are still pockets of community within and outside the art world. For every edition of the biennial, some form of unexpected collaboration or support always springs up at the last minute. This clearly defines the Lagos spirit of community. To our greatest surprise, French/Turkish artist Deniz Bedir, who created the installation titled Taşlık Kahvesi, a relaxation and meditation spot within the square, offered tea to artists and guests alike for the duration of the biennial.

ss: How did you manage to finance such a big event? Did the financial dimension of this project bring up political discussions and choices within your team?

That’s the big one! Blood, tears, sweat…and some prayer. Much of the funding came from international organisations like the Open Society Foundations and the Terra Foundation for American Art. The rest came from private individuals and art collectors within and outside the country. We also had travel support from Royal Air Maroc. What is more important than funding is a clear and distinct curatorial premise. It is quite easy to create another biennial or exhibition with familiar staples. The difficult part is creating experiences and optics outside our collective scope of reference. I cannot for certain say that we achieved this, but at least this was the drive. Biennial aesthetic is relatively straightforward; one biennial pretty much looks like the other, so you always have to strive to create something unique.

Did the works you saw during this biennale allow you to find something you couldn’t see in your research?

Not necessarily. It made me believe more in the relevance of the research and its timeliness. I picked perspectives and pockets of information during the biennial; still, the premise of my research is establishing the validity of monuments from the West African post-independence period as sites for heritage production. So, no, I’m not surprised when the heritage is produced 🙂