Yto Barrada

Holes in the moon

Invited by the Ecole nationale supérieure d’art de Paris Cergy (ENSAPC) for the event « Un été culturel en Île-de-France », the Franco-Moroccan artist Yto Barrada has installed an Arabocentric calendar of the lunar cycle on the facades of the ENSAPC.

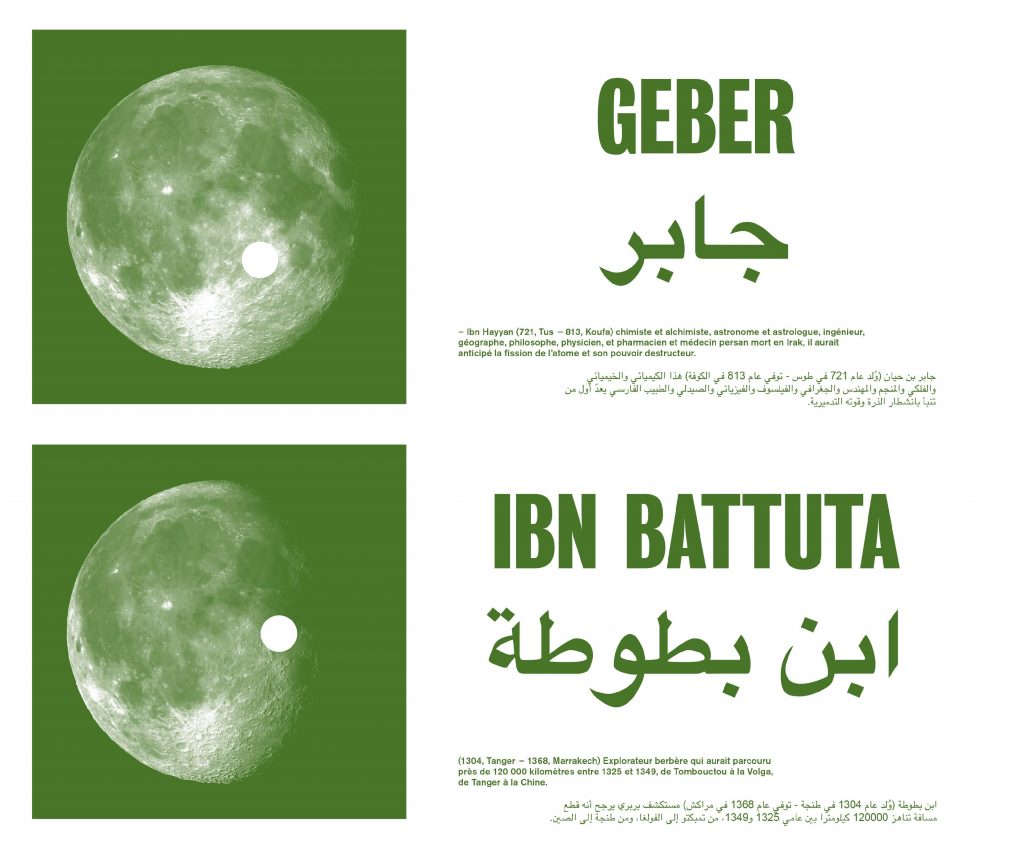

Each of the twenty-five phases of the moon visually highlights one of the craters named for Arab or Islamic scientists. The Moon’s surface is riddled with holes; these craters, most of them the imprints of long-forgotten asteroids. Also long-forgotten are the names of many of those who first discovered and studied them —along with empty spaces in the history of lunar conquest; and the telling holes in the legislation which relates to its occupation and exploitation.

As often in her work, Yto Barrada develops here an interest in history and storytelling, and special forms of knowledge which constitute both.

THE CONQUEST OF SPACE BEGAN REMOTELY AND THROUGH LANGUAGE

Long before astronomy tools, long-view optics or aerospace, it was human imagination that explored the moon’s surface. From our neighborly distance, we recognized in the facets of the moon human and animal figures, and a geography close to our own planet : high mountains and hollow valleys for Democritus, seas and continents for Leonardo da Vinci … The calculations of scientists and then the first optical glasses progressively led to further observations, new maps — and coveted naming rights.

Naming is a performative act: when I give you a name, I attribute you to someone or to something. Any “given name” signals appropriation, and is based on some ideology. Most naming ceremonies are also honorary operations and contracts of affiliation.

Twenty-five of the lunar craters are named after Arab or Islamic astronomers. The names adopted in 1935 were given a latin form: Alpetragius, Albataneus, Alfraganus, Averroès, etc. Some were Arabs whose origins had been forgotten: Avicenna’s real name is Ibn Sina.

There are no women among them. The complete list of craters includes about twenty female observers, an ironic minority for a planet considered as a biological clock of the female body.

As movements pull down the statues celebrating the abuse of power, and the rejection of once-dominant histories in the public space expands across many countries, it is good to look at how far our fables travel. Thus Barrada seizes on the ideal space of projection: the moon.

SCIENTISTS IN THE SKY

Selenography, the study of the physical features of the Moon, became systematic in Western civilization by the end of the 15th century AD. The first lunar toponymies refer to the great Greek and Latin figures, to mythology, and especially to Catholicism. The nomenclature of the various craters evolved until 1935, when the International Astronomical Union (IAU) formalized the list and the rules of attribution. During the 1950’s, satellite imaging helped map more than one thousand three hundred craters, which all bear the name of scientists— mostly men, mostly Westerners.

As Apollo 11 launched in 1969, Ralph Abernathy, a friend and ally of Martin Luther King Jr., led a procession of five hundred people to Cape Canaveral to protest the disproportionate cost of the lunar project, at a time when around one fifth of the American population lived below the poverty line. Two mules pulled a wooden cart to signify the technical level of technology accorded to African Americans; protesters damned the conquest of space as an “inhuman priority.” The following year, writer and musician Gill Scott-Heron sang in Whitey on the Moon: “No hot water, no toilets, no lights / but Whitey’s on the moon. Was all that money I made last year / for Whitey on the moon?”

The highly scripted “giant leap for mankind” has primarily fascinated Westerners; for others, those steps have felt like an expensive piece of Cold War propaganda.

THERE IS SILENCE IN THE TREATIES

With the Outer Space Treaty of 1967, the United Nations banned the military appropriation of space and celestial bodies. In 1979, the Moon Treaty attributed all celestial bodies to the international community and prohibited any exploitation of them. But the Treaty was never ratified. By separating the ownership and the exploitation of space, men created a legal vacuum — with holes and loopholes in the law. So the moon could soon be full of geologist’s test holes as well.

The SPACE Act, signed by President Obama in 2015, granted commercial exploitation rights to private corporations. Last April the Trump administration pushed the matter further, arguing that outer space is a legally and physically unique area of human activity, and the United States need not treat space as a globally shared asset.

Planned projects on the moon have multiplied. What are these earthlings really doing up there? We might well wonder if this cyclical icon of the inaccessible and the unknown, this dream signal and blank screen for the projection of selfhood into another world, can still provide a diversion from the mistreatment we have inflicted on our home planet … Though the lunar atmosphere is truly unbreathable, plans to colonize the moon claimed to offer a reassuring counterpoint to the disastrous state of the earth.

Are we still looking at the world in terms of exploitation? Is the moon a new territory to colonize? To privatize? Really ?

Planet Earth, 2 August 2020, Marie Muracciole.

Yto Barrada (b. 1971 works and lives in New York) is a Moroccan-French artist recognized for her multidisciplinary investigations into cultural phenomena and historical narratives. Engaging with archival practices and public interventions, Barrada’s installations uncover lesser known histories, reveal the prevalence of fiction in institutionalized narratives, and celebrate everyday forms of reclaiming autonomy. She is the founder of Cinémathèque de Tanger, an arthouse cinema and a cultural center that has become a landmark institution bringing the Moroccan community together to celebrate local and international cinema.

Barrada’s work has won numerous awards including the 2019 Roy R. Neuberger Prize, the Rotterdam Film Festival 2016 Tiger Award for short film, a nomination for the 2016 Prix Marcel Duchamp, the 2015 Abraaj Group Art Prize, the 2013 Robert Gardner Fellowship in Photography (Peabody Museum at Harvard University), and the 2011 Deutsche Guggenheim Artist of the Year award.

Her work is held in the collections of, and has been exhibited at, the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York), Tate Modern (London), The Museum of Modern Art (New York), Guggenheim (New York), Centre Pompidou (Paris), Serralves Museum (Porto), Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien, Canadian Centre for Architecture (Montreal), among others.

Yto Barrada is represented by Sfeir-Semler Gallery (Hamburg, Beirut), Pace gallery (New York, London) and galerie Polaris (Paris).

Marie Muracciole, the curator of this project, is an art critic and art historian who lives in Paris, having previously directed the cultural department of Jeu de Paume in Paris from 2005 to 2011 and the Beirut Art Center in Beirut from 2014 to 2019.

ENSAPC would like to thank Marc Touitou and the studio Huber/Sterzinger for their precious contribution to this project.

With the support of the culture programme of the region Île-de-France – Ministry of Culture.